**This is an up

**This is an up

In 12 months here, at the Institute for Software Research master programs “cave” (it’s actually a really cool facility, we just like to call it a cave like all the SE students did before us), I learned more than what any uselessly exhausting, principle-and-reflection-free, “constant chaotic firefighting mode” professional experience would have taught me. And as a confirmed 90s geek, I will go ahead and quote Neo from the Matrix: “I know Kung Fu”, although in my case it was not a simple “hit enter” action, it was probably the 12 most challenging months of my life.

My classmates and I can make many statements like that now! “I know software architecture”, “I know code analysis”, “I know software project management”. And here’s the interesting part: not everyone learned the same or captured all the topics equally. Some people enjoyed management classes more, and will probably go on to become successful managers. I was personally quite fond of our Architecture, DevOps and Engineering Data Intensive Scalable Systems courses. Overall, I think that’s where I improved most: I can now tackle big system/software engineering problems confidently, backed by knowledge I didn’t even know existed a couple of years back, when I was a junior software development engineer struggling to learn in my corner about how to build “good software”.

It is mostly thanks to the unique chance of learning from some of the brightest professors and instructors of software engineering disciplines in the world (they have actually been setting standards in many SE areas), but also because the US higher education system is way more advanced than the ones I evolved in before, i.e. the Tunisian and French systems.

Here, people cut to the chase: you learn from the source (books, articles, etc.) about what you came here to learn, you do the learning by yourself, and you’re simply guided through it. Assignments, quizzes and projects make sense. They have goals, a purpose, a meaning. You learn something new, you acquire a new skill, a new technology, etc.

In France, they have “grandes écoles” (literally “great school”, yeah, I know, right?), and you know what? I learned more towards becoming a maths teacher than I did towards my actual major! The French (and their former colonies by extension) are obsessed with this weird idea that to learn engineering disciplines means to learn pure hard theoretical math. I kid you not. Even grade-wise, math classes outweigh everything else in engineering schools there. It bothered me so much, I mean they had us learn theorem proofs for god’s sake! It disappointed me, I was lost for a couple of years, felt like I was wasting my life (which I was actually), and eventually had to quit because even when I tried to convince myself that I’m now invested in this path and should stick to it to have a future, I was not even doing the work anymore, and ended up dropping out. At a certain point in that period I actually even questioned my preference for engineering and thought I’d switch to languages or journalism. It was that bad. It worked with most people, it simply didn’t with me.

In Tunisia things were much better. Although I actually kept doing unnecessary math for my major, it was lighter and more application-oriented. I took some excellent courses from some great teachers whom I remember fondly to this day and will forever, but some courses were not that great. As it is the custom in Tunisia, corruption and incompetence found a way of slipping two or three people who frankly have nothing to do with teaching CS into one of the best CS departments in the country. My classmates and I ended up paying the price for that in wasted time. But to be honest the good outweighed the bad, I was happy with what I was learning, and I got the chance to do many extracurricular activities.

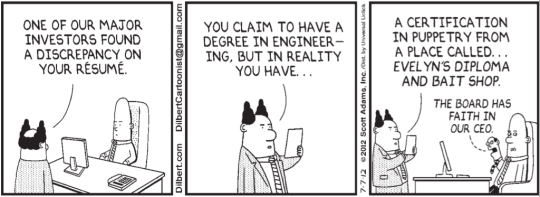

So bottom line? Not all degrees are alike. The degree itself is still a mere tool, a credential (an important one for that matter), but your worth as an engineer has to be proven again and again with every problem or challenge that comes your way. Your worth as an engineer is about consistently doing your work successfully, using the principled approaches you learned. That’s what engineering is, a constant challenge.

I often like to use this metaphor: a good degree helps you break the glass ceiling blocking your career ascent. But a great degree would require you to acquire valuable knowledge and skills in the process.